- Home

- James A. Burton

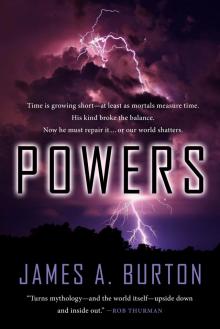

Powers

Powers Read online

POWERS

James A. Burton

Copyright © 2012 by James A. Hetley.

Cover art by Matthew Hughes.

Cover design by Telegraphy Harness.

Ebook design by Neil Clarke.

ISBN: 978-1-60701-365-5 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-60701-336-5 (trade paperback)

PRIME BOOKS

www.prime-books.com

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

For more information, contact Prime Books at [email protected].

For Lucienne, agent extraordinaire.

I

The air hummed, oily golden liquid condensed out of sparkling haze, and a demon took human shape across the kitchen table from Albert Johansson. The thing stood at an angle to the world until it put one glowing hand on the scarred Formica tabletop and twisted to vertical without apparent movement, as if concepts of up and down were optional and it had to locate itself in space. It smiled. The smile showed too many teeth for comfort. Large needle-pointed carnivore teeth, suitable for ripping flesh—living or dead, human or other, it didn’t matter.

Albert froze. He sniffed. Nothing. No brimstone, no incense, no arctic chill or furnace heat or moldy damp earth-smell of the unquiet grave. Nothing. And he trusted his sense of smell, closer to hound than human. His nose told him that the form, those teeth, weren’t even there.

Then, as if he’d asked for it out loud and the demon thought to add another sense and more reality to the scene, an ozone tang of nearby lightning spread through the room and stung his eyes.

Albert tore his gaze away from those teeth and stared at the hand instead, wondering if now the plastic would begin to smoke and bubble and char. Or maybe freeze and shatter with bitter cold. You never knew with demons.

Nothing happened. The hand continued to be a golden hand with the dull luster of true pure metal. The table continued to be a table, no more worn and scratched and battered than it had been before, pale green plastic-laminate top with a pattern of faded almost-daisies to disguise spills and stains, zinc edging with the dings and dents of fifty years of abuse.

More nothing happened.

Albert blinked three times and took a deep breath, feeling ice settle into the pit of his stomach and spread chills out to his fingers and toes. He’d been minding his own business, building a sandwich at his kitchen counter and listening to Bach’s solo cello suites, intellectual and sensuous at the same time. Home-baked dark chewy rye—baking bread cost time rather than money, and he had a lot more of the former than the latter. Besides, he enjoyed baking bread—the smooth warm resilient touch of kneading the loaf, the earthy living smell of first the damp flour and then the rising yeast followed by the baking. It never got boring, even after a few hundred years.

He was passionate about good food and good music. Damned little else, and his apartment reflected that—peeling wallpaper, cracked plaster, stove and refrigerator and furniture that had seen better decades or centuries rather than just years. But he couldn’t quibble with the rent. His family owned the place.

He should have been safe and private, savoring first the thought and then the deed—fresh-baked rye bread just cool enough to slice, parchment-thin salty dry Westphalian ham layered with nutty Emmenthaler cheese, fragrant and full of holes, brown stone-ground Raye’s ginger mustard from a century-old mill powered by the giant tides in the Bay of Fundy . . .

The room had hummed around him and he glanced up and this golden ectoplasm materialized next to his kitchen table and took the shape of a man. Demons, angels, spirits, djinn, whatever you called them—they didn’t usually waste time with doorbells. They didn’t have to. At least this one hadn’t felt the need to manifest with a clap of thunder and cloud of brimstone smoke. Or blast the apartment door into cinders and flinders for the dramatic entry of a desert whirlwind.

He’d seen that sort of thing in his long, long life. It stuck in his memory. He had forgotten a lot of things, important things, over the centuries, but that sort of thing he remembered. Demons had that effect on people.

It didn’t seem to care whether Albert knew its true nature. It didn’t bother with clothes. Neither male nor female, no visible genitals, no nipples on a chest shaped halfway between pectoral muscles and breasts. No bellybutton. “Man” as “human.” Sort of. Or at least that was what it showed to him. Other eyes might have seen other forms. A burning bush, maybe, or wheels within wheels within wheels.

Or maybe they wouldn’t have noticed anything at all. Sometimes Albert saw things that others thought weren’t there, heard words that other ears ignored. It was part of being what he was.

Whatever that might be.

He took a couple of deep breaths. He blinked and felt cold sweat breaking out along his spine. The demon was still there. He cut the sandwich in half and put it on a plate and offered it. The demon grunted its thanks, pulled out a chair and sat on it without even singeing the wood, and Albert started to build another sandwich.

Thoughts spun through his head. What the hell am I supposed to do now? Fall on my knees and genuflect and pray? I’m not sure there is a fixed etiquette for such meetings. If they want you to take off your sandals because you stand on holy ground, they’ll tell you. If they want to rip your head off and crunch it for an appetizer, they’ll go ahead and do it.

One did just that to Johannes. Brother or not—from what Mother told me, the damn fool asked for it. Elaborate suicide. I’m not that bored with life. Yet.

He’d lived long enough to see plenty of weird shit. He’d seen friends die in agony or wish they could, had plenty of enemies try to kill him and fail. He’d had a few centuries of practice in keeping calm under pressure. Sometimes it helped. But his hands shook enough that he had to concentrate on spreading more mustard, layering more ham and cheese. Angel or devil, it didn’t matter. Long history said that visitations from either tend to be rough on the neighborhood.

He stopped working on the sandwich and studied the knife in his hand. He loved good food, good music, and good iron. Iron and steel and him, they understood each other. They talked to each other.

Most people would look down at him and sneer at the idea that he was a master smith—him standing maybe five foot three on a day when he was feeling tall, and no more muscle than most people his size. But good smithing, that wasn’t a thing of forcing metal to do what you wanted. It was more a discussion and persuasion, not domination but partnership. He did blades and fine-work and didn’t need a lot of bulk to heave cart-horses around for shoeing. He just had to set his anvil a little lower than some others in the craft.

His kitchen knives had been an experiment—nickel-iron born from a meteor’s corpse, to give each blade the flaming magic of steel pulled from heaven to earth by the implacable drag of gravity, steel worked and folded and folded again at the forge, carbon infiltrating the grain of the metal from a reducing fire, thoughts and words of making until the steel took meaning from his hammer, a shape and meaning that maybe could skin and gut a god and chop him into cubes for stew meat. The blades could slice a tomato paper-thin as well, or bone a slaughtered cow, and he only needed to sharpen them once a decade. He wondered what would happen if he leaned across the table and stabbed this knife, this living knife, into the body of the demon.

But he wasn’t about to try.

He finished building the second sandwich, sliced it in half, and put it on another plate. He grabbed a bottle from the refrigerator—dark Shipyard ale, strong-hearted enough to keep company with the sandwiches—waved it in the direction of the demon and got a smile and nod of acceptance. At least its mommy had taught it not to talk with its mouth full. If demons had mommies . . . .<

br />

So he opened the bottle, poured straight down the middle of a glass to let the bubbles breathe into a good head, and opened and poured another for himself. Before his knees collapsed under him, he sat down. Sat down on a worn scarred wobbly-legged blue-painted wooden kitchen chair, about as mundane as it gets, across his battered 1950s yard-sale kitchen table from a demon. With a ham sandwich and a beer. Surreal. It had rattled him enough that he’d forgotten the pickles, had to get up and open the refrigerator again and look a question at the demon. Again, it nodded that it would like one. Strong sharp Kosher dills.

Kosher. Like ham and cheese sandwiches maybe slipped past Leviticus? But that’s why he kept thinking of it as a demon. Legend said that angels kept Kosher, demons didn’t. Albert wouldn’t know. He’d only met two, maybe three for sure, never had offered one a sandwich, and the last was more than a hundred years ago. He knew the theory, but half-remembered legends didn’t compare with smelling ozone in his kitchen and then sitting down across the table from the Other.

He couldn’t even tell if there was a real difference between angels and demons, or if that was just a label we put on a mirror that reflected what we found inside ourselves. Taxonomy of the spirit world got awkward. It was too . . . other.

Anyway, it ate the sandwich and the pickle in alternate bites, drank the beer, belched. Albert wondered if he should ask some priest or rabbi or mullah whether it had to shit afterward. As far as he knew, spirits didn’t need food, but this one seemed to enjoy the snack. It belched again. Maybe it wasn’t used to beer.

Or maybe it hung out in a society where belching after a meal offered compliments to the chef. Albert knew such places, such people, from centuries of travel.

“Simon Lahti, I thank you for bread and salt. A blessing be upon this house.”

Albert twitched at the name. He’d used dozens, maybe hundreds, moving from place to place down the years. It got to the point where he had to concentrate, remembering just who he was supposed to be this year and city. That name went way back. And then there was the angel/demon thing again. Demons were supposed to go in more for curses than blessings. Maybe it was trying to keep him off balance. If so, it was doing a damned good job.

Its voice sounded . . . peculiar, again neither male nor female, but with a hollow resonance that didn’t seem to fit that pseudo-chest, more like the echo of an oracle’s cave. It stopped there and looked at Albert as if expecting some kind of ritual response. The man nodded and looked a question. His tongue didn’t seem to be working right just then.

“Simon Lahti, we wish you to act for us.”

A heap of coins formed out of nothing and clinked together on the table. They looked like gold. The ones Albert could see looked like old U.S. “eagles” and “double eagles”—ten- and twenty-dollar gold pieces, last minted in the 1930s. He picked up a palm-full. Heavy, heavy, heavy in his hand, the way metal money used to mean something serious, and it took him back a ways. Some fives and even tiny ones mixed in. Different dates—1880s to 1920s—different designs, different scratches and dings and level of wear, as if they’d come from a real hoard rather than minted fresh by magical imagination.

A large heap—somewhere between five hundred and a thousand dollars in face value, he guessed, more money in one place than he’d seen in years. Hell, in decades. Sold piecemeal to collectors, he could eat well for years off that pile.

Living in fuzzy shadows of the modern world, using borrowed names and forged papers, he’d never make that kind of money in a daylight job. That’s why he lived on the fourth floor of a slum that wanted to collapse into its cellar, eating beans more days than not.

Cassoulet with lamb sausage, chili in a hundred variations, home-baked beans, no reason they had to rank as fodder. His brain chased after that tangent to avoid thinking about the demon. Yellow-eye beans soaked overnight, add chopped-up onions and garlic, a good chunk of salt pork, molasses, ginger or mustard, sometimes sliced Greening apple. Slow-baked, all day in the oven blending those flavors and perfuming the air, and the pizza joint downstairs paid for the gas. Served them right—lousy pizza, skimped on the sauce and cheese . . .

He dragged himself back to present danger. What he did next probably wasn’t smart. He did things like that now and then, things that gave him the total shakes when hindsight kicked in. Then he’d start thinking about his brothers, the ones he knew about, and his sister, and how their stories all ended with them seeking death. And finding it.

He stood up, walked over to the old gas stove, and dropped three coins into a cast-iron skillet he’d left out to dry over the pilot light after washing up from breakfast. Clinkety-clinkety-clink, the proper sound of gold hitting iron, they bounced and rattled and settled and stayed put. They didn’t vanish with a sizzle and puff and a stink of rotten eggs when they touched cold iron. Not fairy gold.

He picked them up and turned back to the table. The demon’s “face” looked vaguely amused. Or maybe not—Albert didn’t have that much experience in reading demon expressions.

That’s the point where second thoughts kicked in and he realized the chance he’d taken. He could have ended up as a smeared layer a molecule or two thick, adding fresh stains to the peeling wallpaper, for insulting his visitor. He wished his brain worked faster, but he’d never claimed to be a genius. Just slow and steady and persistent to the point of pig-headed. Mind or body, he wasn’t built for speed.

He bulled ahead, his usual move when he stepped in that kind of shit. “Who wants to hire me? What do you mean by act?”

“Our name is Legion. One of your kind has been abusing our companions. We wish you to stop this abuse.”

Companions. Albert sorted through memories of Mother by gaslight, or did that flickering yellow gleam in her eyes come from a candle, an oil lamp? A fire at the mouth of a cave to keep the dire wolf and saber-tooth at bay? Tales in the drowsy fog before sleep, anyway, tales of the land where she was born across the sea or under the mountain or in flying castles above the clouds.

Too many tales, too many words, with no proof that any single word was true. Mother could weave a tale that made you smell the spilled guts of fresh-dead corpses on a battlefield and hear the rustle of raven wings over the groans of the dying, then the next day tell another story with the same heroes very much alive ten years or ten centuries later.

Companions. Companions to spirits, demons, angels—not pets, as such, not something owned. Not something equal, either.

Elementals.

Sprites of earth, wind, water, fire, not things of thought and speech and reason. The heart or soul of the grove, the spring, the stone, the mountain cave, the deep and darksome tarn. Blue flame dancing free of the coals of a dying cook-fire.

And someone had been . . . abusing . . . them. This could get messy.

“Why don’t you deal with the problem yourselves?” Hey, King David or Elijah or some other Bible guy got away with arguing with God. This was just a demon.

Mother had warned Albert to never trust a demon. Legends again, most cultures—demons didn’t care what happened to mortals, and they seemed to enjoy playing tricks. Plus, they twisted language for their own amusement, seeming to promise one thing and then delivering something quite different. Nasty different.

The demon squinted at Albert, as if it read his mind. Maybe it could. “Your kind created the problem. Your kind must deal with it, or face the consequences.”

Talk about guilt by association. “Consequences”—Albert didn’t like the sound of that. Brought up images of Sodom and Gomorrah, it did. Another example of why he didn’t really care whether he was talking to an angel or a demon. Either could be just as rough on innocent bystanders.

Not really. His brain ran off on another tangent, still trying to dodge. Angels generally get the worst of any comparison. Demons tempt or torture individuals. Angels visit the Wrath of God on whole cities or tribes or nations and they don’t bother to file an environmental impact statement first.

“Why

me?”

As soon as he said it, he realized how silly that sounded. He’d meant it as an actual question rather than the classic whine of Job goosed by God’s fickle finger. Why do they want to hire me, rather than a detective or some wizard or perhaps a priest? I’m just a maybe-man who has managed to live a long, long time, and forgotten most of it.

Detective, wizard, priest. In all the various and nefarious ways I’ve earned or stolen a living, I’ve never been a detective. Outside of a special bond with iron and steel, I don’t have enough magic in my whole body to light a match without striking it on the box. I’ve never been able to sort out the true Word of God from the lies men spin as easily as they breathe. Like I said, why me?

At that point he decided he needed another beer. Maybe the demon wanted another, too. He had no idea what effect alcohol had on the spirit world. If he’d stopped to think about it, the vision of a drunken demon probably would have pushed him over the edge to run screaming down Main Street. But the demon nodded when he waved another Shipyard in its direction. Albert pulled a fresh six-pack out and set it on the table between them, no reason to stint. Hell, he might not live to finish another.

The demon smiled. Albert thought it was a smile. It still showed too many pointed teeth and a hunter’s eyes, like a leopard or wolf shape-shifted into human form. “You see things that others do not see. You hear things that others do not hear. You do not seek dominion over men. We know that you respect our companions.”

It gestured toward the living room on the far side of the kitchen doorway, at the old fireplace that used to be the sole heat of the room, back when Albert’s family first bought the pile of crumbling brick and dry rot fronting on South Union. Four fireplaces on each floor, originally, one drafty pitiful heat-waster for each of the front and rear rooms of this deep narrow row-house apartment, with a long cold tunnel of space in between. Say what you want about the sad decline of civilization and the golden Elder Days, Albert thought central heating and flush toilets were grand ideas.

Powers

Powers